Major Food Crisis in Hawai’i at Mid-Century

by Dr. Kioni Dudley

July 2017

(Please note that, because the topics in this paper are new for many readers and are likely to be

questioned, documentation from sources widely recognized as authorities is given in endnotes.)

Executive Summary

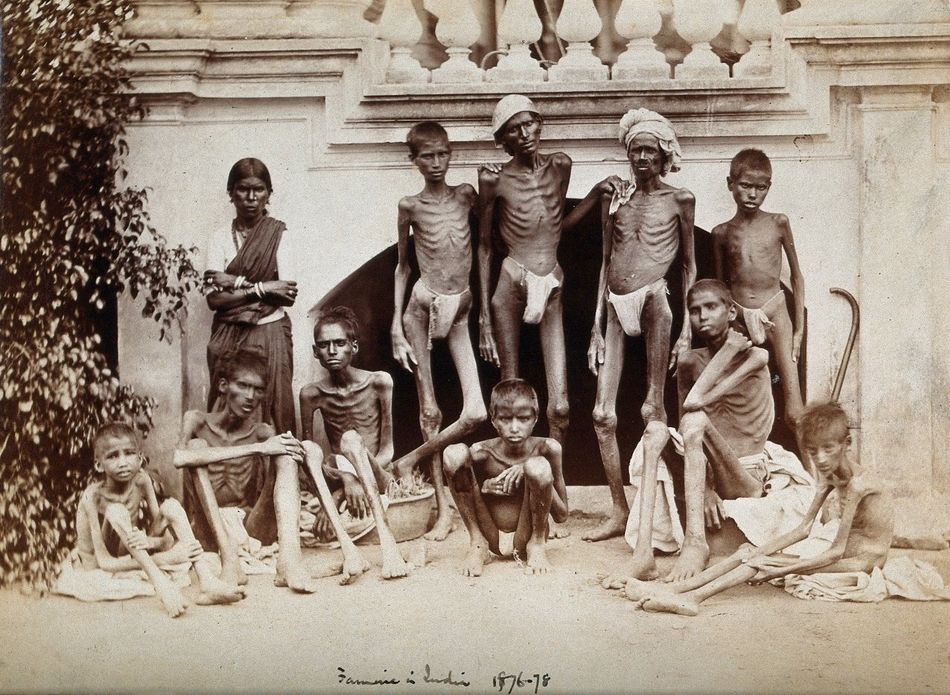

It’s out there. It’s a killer like we’ve never known. Warnings from the United Nations are growing more frequent, more insistent, more urgent, and more dire. But America is not paying attention. And few in Hawai’i are even aware.

The killer is world population explosion. By 2050, we will struggle greatly to feed all of the new people. Famine and starvation will grip major parts of the world. Prices for the food that is available will soar astronomically. And there well may be no food available

for Hawai’i to import at any cost, just thirty years from now. Wheat, potatoes, beef, eggs, milk--none of it!

We currently import 90% of what we eat. We keep a one-week supply on-island. We must completely reverse current practice. We must hold onto all current farmland, quadruple our farm acreage, bring back cattle, pigs, and chickens, and become one hundred percent food-self-sufficient in the next thirty years, to keep our million people from joining the hundreds of millions worldwide who will be enduring famine and starvation in the latter part of this century.

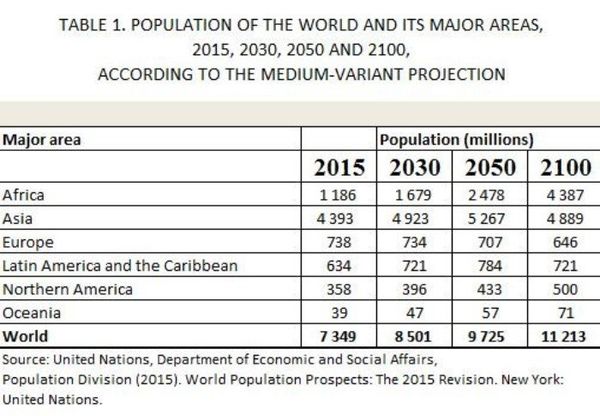

Exploding World Population

When people now in their 70s were born, there were 2 billion people in the world. Now there are 7 billion. Think about it. From the time the first humans walked the earth two and a half million years, it took up until the 1930s for the population to reach 2 billion. But in the next forty years, it doubled to 4 billion. And in the next forty years, that 4 billion has doubled to nearly 8 billion. The world currently adds 1,600,000 additional people to the population every single week. The U.N. projects that growth will slow, and that the population will only reach 9.7 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100. 1

To feed the world population by 2050, the United Nations tells us that we will need to increase world food production 100%. That is, food production must double by 2050 to meet demand from world’s growing population. 2

Let that sink in: for every single bite of food in the entire world today, there must be two—in just three decades.

Food Production Must Double by 2050 to Meet Demand from World’s Growing Population, Innovative Strategies Needed to Combat Hunger, Experts Tell Second Committee

https://www.un.org/press/en/2009/gaef3242.doc.htm

Shrinking Aquifers, Desertification, and Maxed-out Farm Expansion

A stunning article in the August 2016 National Geographic Magazine, which inspired this writing, details the huge problems we face in doubling food production. 3

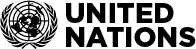

To start with, more food production takes more ground water. But the terrible truth is that, over the last four decades, providing sufficient water for ever more farms to feed the rapidly growing population of the world has already decimated world aquifers. As the National Geographic article says, “NASA satellites have found that 22 of the world’s 37 largest aquifers have passed the sustainable tipping point.” They will never again be able to meet the water needs of all their users. They can only keep shrinking. This shrinking of aquifers across the world is happening at the same time that exploding population is demanding more water for greater food production. As recently as June 6, 2017, the Secretary General of the United Nations warned that by 2050 global demand for fresh water is projected to grow by 40 percent, and at least a quarter of the world’s population will live in countries with a “chronic or recurrent” lack of clean water. 4

Water is not the only problem. Desertification, caused by climate change, overuse of land, and cutting forests is a growing problem. Thirty-three percent of the global land surface is now desert. More than one billion people are affected by this expansion, half of whom live in Africa. 5

Further, a number of countries, particularly in North Africa, the Near East, and South Asia have already reached or are about to reach the limits of land available for agriculture. 6

These are the same places where water scarcity is reaching alarming levels. 7 Unaware of the fate that awaits them and their children, the populations of 28 African countries are projected to more than double between 2015 and 2050.

8

370 million starving in 2050

If we lived in a world of true brotherhood of mankind, everything could work together in a best-hope scenario to prevent the coming calamity. As nations would move into the first world, birthrates would decline. Amazing strides might be made in greater food productivity and in water conservation. We could possibly grow enough food and ship it to those who need it. It could all work together. 9

But we are not a world brotherhood. On March 11, 2017, the UN humanitarian chief stated: “Already we are facing the largest humanitarian crisis since the creation of the United Nations. More than 20 million people across four countries are now enduring starvation and famine.” These people of Somalia, Yemen, South Sudan, and Nigeria could be fed, but wars and man’s inhumanity to man are preventing them from growing food or reaching outside food. It is important to note that these wars all began because of lack of food. We should only expect more of this in the future. As aquifers dry up and enough food can’t be produced, there will be battles over what food there is, and migrations of peoples to places better off. Migrants will be met by armed forces keeping them out so their own people can eat.

Unless the world begins working together to solve all of this, the United Nations predicts that 370 million people will be starving in 2050. 10

And it could be far worse: The population is not growing 2-4-6-8-10; it is growing exponentially, 2-4-8-16-32. If U.N. projections of a slowing in population growth are wrong and it keeps doubling every forty years, instead of 9.7 billion people in mid-century, we could have 16 billion. And instead of 11.2 billion by 2100, we could have 32 billion. 11

There is absolutely no way that the world could feed this number of people.

America Not to Be Spared

America is also vulnerable. In spite of our low birthrate of 1.9 - 2.0 children per family, 12

U.N. reports place us as the seventh fastest growing nation in the world. 13

And we have major food problems.

The United States is no longer a net exporter of foods. That reversed in the 1990s. The gap between imports and exports has grown from $0.5 billion in 1990 to more than $11 billion in 2015. 14

Our largest aquifers are also beyond their tipping points. Because of increased farming, the Ogallala Aquifer which runs under our central bread basket all the way from North Dakota to Texas, dropped another foot last year alone. Due to over-pumping, it has lost 60% of its water in the last 60 years. 15

Many farmers in its shallower areas have already completely run out of water, which will never be restored. 16

On a map of the world’s thirty-seven largest aquifers, the Ogallala Aquifer is still colored pale green. But it is one of the twenty-two that have reached their tipping point.

The even larger Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plains Aquifer which stretches down the lower Eastern seaboard and underlies all of Florida, and lower Alabama. Mississippi, Louisiana, and coastal Texas is colored orange, clearly distressed.

Picture of the 37 largest aquifers in the world. Note how bad off America’s are.

Groundwater storage trends for Earth's 37 largest aquifers from UCI-led study using NASA GRACE data (2003 – 2013). Of these, 21 have exceeded sustainability tipping points and are being depleted, with 13 considered significantly distressed, threatening regional water security and resilience.

Credits: UC Irvine/NASA/JPL-Caltech

California Breadbasket in Trouble

And the California Central Valley Aquifer, underlying the most productive area in America, the San Joaquin Valley, is solid red. 17

It can only shrink with every coming year. Six years of drought have left thousands of dry wells in the San Joaquin. 18

Lack of water is not the only problem in the San Joaquin Valley. The valley lay undersea for 60 million years, and the residue salt in the soil washes away with irrigation and has accumulated in a toxic lake that cannot be drained. Enormous amounts of salt and selenium - toxic to birds, other wildlife and humans at high concentrations - continue to accumulate each year. Following many Federal studies, the Fish and Wildlife Service has concluded that the best solution is to "remove the fundamental underlying source of the problem" by retiring 379,000 acres of land from irrigation. 19

This is all happening at the wrong time. The San Joaquin Valley supplies one third of the fresh produce for America 20

and is a major supplier for Hawai’i.

Today, the population of the US is 303 million people. In 2050, it will be 438 million. 21

For every 3 people we feed today, there will be an additional 1 ½ mouths to feed...in just three decades. Meanwhile, rising temperatures, less rainfall, desertification, and receding aquifers all will fight against the additional crop production it will take to do the job. Mainland America, already a net importer of food, will be stretched to its limits trying to feed its own people.

Hawai’i Imperiled Must Wake Up

There is simply no chance that Hawaii’s massive importation of food will not be greatly disrupted, if not turned off completely.

However, none of this is on our radar in Hawai’i. Hardly anyone is aware that it is even happening.

As noted above, we are almost completely dependent on imported food, bringing in 90% of what we eat, and keeping only one week’s supply of food on-island. As food becomes more scarce, prices will skyrocket. It may become too expensive to import most foods. Or worse, by 2050, it is quite possible that there will be no outside food available to import, from anywhere. We must prepare for this fact or we will die. In just three decades, we need to be totally self-sufficient in food. In our spirit of aloha, we should also look at not only providing for ourselves, but to producing food for export to a world in need.

Our government needs to be awakened to the urgency. This year, the governor reset his goal to double food production by 2020, pushing it ten years later to 2030. Then he changed it back to 2020.

At a January 7, 2017, hearing of the House Finance Committee, Chair Sylvia Luke told the head of the Department of Agriculture that it didn’t really matter whether the goal was 2020 or 2030 because it was a “fake goal” anyway. “It’s a fake goal because we don’t even know where we are starting and where we want to end up and how do we get there,” she said.

In a Star-Advertiser article, the director of the state Department of Agriculture acknowledged that “there has yet to be any significant increase in local food production, though he noted that plans to increase local egg, dairy and beef production are in the works.” 22

In this year’s session, the State legislature looked like it was going to take some action, seeming to strongly support SB 1313 which would have required the Department of Agriculture to establish a strategy and goals for increased food security and self-sufficiency. But the bill died in committee. No one in government seems really aware of the urgency--to get moving, not to just make plans.

Whitmore Project and its Limitations

Senator Donovan Dela Cruz has been making efforts to revitalize farming in his own district, Wahiawa-Whitmore Village. He has been successful in getting the state purchase to large tracts of land and buildings for his Whitmore Project. 23

All of the land lies just north of Wahiawa, and borders the 1700 acre Galbraith Estate which the state purchased in 2012 to supposedly relocate Aloun Farms and Jefts Farms from Ho’opili to this higher ground.

But while this Whitmore Project may eventually revitalize agricultural production in the highlands around Wahiawa, the land involved is some of the most difficult to farm in the state because of the large amount of rain it receives and the frequently overcast skies.

After decades of working for Dole Pineapple, a source wrote: “In those days, Central Oahu farmers needed to expect DAILY, at 4 pm, heavy, heavy rainfall, May-September. From October to April, they may as well shut down, stop farming to minimize farmers’ risk. Tractors always needed to pull pickup trucks stuck in mud buried to their axels.” 24

Leon Sollenberger, an agricultural services contractor who has worked the area extensively as a tiller, writes: It is true that there is not much that simply can't be grown at the higher elevations, but certainly there will be reduced yields, and there will be parts of the year that some crops won't grow. Corn doesn't do well at all at the higher elevations, especially in winter. Most of the yield decline will be in slower growth, smaller final size, and no crops grown in the winter. Some of that is due to excess cloud cover and rain, and some of it is due to field conditions (mud) that make machinery difficult or impractical to operate. 25

The Galbraith land was so difficult to successfully farm that for years before it was sold to the state, Del Monte Pineapple had given up on farming it altogether, letting it lie fallow.

Soil Remediation Needed for All Pineapple Lands

It is not just the recurrent rain that is problematic. All of the lands where pineapple has been grown will need to be remediated before other crops can be grown on them. This is both time consuming and costly. Soil with a pH level below 7 is acidic; soil above 7 is alkaline. The soils in the Central highlands and the north slopes where pineapple has been grown are typically at 4.4, and need remediation. 26

This costs about a thousand dollars an acre and takes two to three years to complete. Most plants cannot be grown on this soil until it is completely remediated. For small farmers, these are monumental problems of time and money. It should be noted that every single acre around Wahiawa and on the North Shore slopes and on the slopes of Kunia that is taken out of pineapple for the growing of other food crops will need this remediation.

An Ulupono Initiative study concluded that if we lose Ho’opili and Koa Ridge, we will need 34,000 additional acres in agriculture to provide the fruits and vegetables needed to feed the people of Hawaii. 27

Many thousands of those acres will need remediation. It’s a task that must be done, in order for us to grow our food on those lands. It will take years to accomplish. It is time to get started.

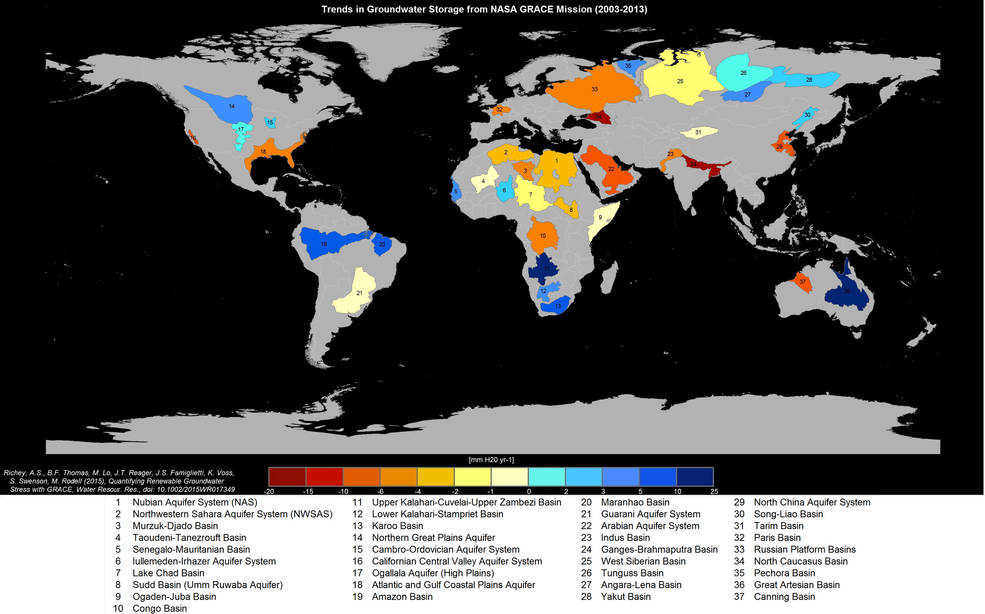

Only Polluted Irrigation Water Available on North Shore Slopes

While the Whitmore Project is concentrated on the upper flatland north of Wahiawa, below it are 3,800 acres of slope lands above the North Shore. Much of these lands will have to be remediated for proper pH level, but they have the additional problem of polluted irrigation water. The Wahiawa Irrigation System, which serves them, uses water from Lake Wilson. One of the Wahiawa Waste Water treatment plants that releases into Lake

Wilson is certified as producing only R-2 water. Because of this, State Department of Health regulations forbid using Lake Wilson water on crops that grow in the ground or on the ground--like onions, potatoes, sweet potatoes, daikon, asparagus, radish, squash, watermelon, cantaloupe, honeydew, and pumpkins—and on crops that expose their edible parts to the sprinkled water, like lettuce, cabbage, basil and other spices, tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, zucchini, etc. Thus, many of the essential crops that we will need cannot be grown on far more than half of the available Central and North Shore farmland. 28

There is a limited amount of land on the southern slopes of Kunia that does have clean water supplied by the Waiahole Ditch. Much of this land will need to be remediated, and all of it opened up for farming of foods that require clean water.

Wahiawa Irrigation System (yellow line) on the north shore slopes of O’ahu

We Can’t Eat Houses

Amazingly, while we are faced with these great problems for the expansion of farming, we are allowing developers to pave over half of the O’ahu farmland actively growing food for our markets today. Ho'opili is 32% of the O'ahu land presently producing food for the local market. Koa Ridge is 13% of the land. Open farmland at UH West O’ahu (next to Ho’opili) is 8%. Together they comprise 53% of the land currently producing our food.

Knowing now of the worldwide food shortages anticipated because of population explosion and climate change, and knowing of the likelihood that by 2050 there may well be no food available for Hawaii to import, and knowing of the great difficulties we face in quadrupling our production of food, it is unconscionable that we surrender this essential 2000+ acres of currently active farmland for the building of unneeded houses. A DBEDT report on housing in 2015 stated that we need only 27,000 new houses on all of Oahu in the next ten years. 29

But we have 52,000 houses already zoned and ready to build in Central and Leeward O’ahu alone without the unneeded homes of Koa Ridge, Ho’opili, and UHWO. 30

Why Save Ho’opili and UHWO farmlands?

There are many special qualities about Ho’opili and UH West O’ahu farmlands that should compel us to keep them permanently in agriculture. Together, they are the last remaining part of what in sugar times was called the Golden Triangle, the highest producing sugar land on the island. The Ho’opili-UHWO lands need no soil remediation: their pH levels are perfect. By holding onto them, we can avoid a twelve million dollar cost for soil remediation of lands to replace them. Professor James Brewbaker has also noted that the Ho’opili-UHWO lands have minimal levels mildews and blights, minimal competition with weeds and thus less need for pesticides, and, for many crops, minimal levels of insect damage. 31

Ho’opili-UHWO also has plenty of clean water for all of its needs. Additionally, the Ho`opili-UHWO agricultural lands are close to markets. And they have the economic advantage of already having in place the infrastructure needed to get product to market--such as cooling and cleaning and packing facilities, and the transportation to get produce out to consumers. 32

Last Warm, Sunny Farmland on O’ahu

In addition to all of that is the fact that Ho’opili-UHWO is the last piece of full-sun farmland on the island of O’ahu. There is no other undeveloped land on O’ahu that has full sun. Everything available is in higher, overcast and rainy areas. It is a common experience when one goes to buy plants at Lowe’s or Home Depot, that one finds some of their plants are in a shaded area and some are in full sun. Buyers are warned that plants that need full sun will not do well in shaded areas. The same is true of farm crops. Many can grow only in specific microclimates. For instance, a new effort by UH to grow chickpeas in Hawaii found that they thrived in some parts of Maui and the Big Island, but not in others. “Just a few miles down the road, Waimea was ruled out entirely as a possible growing site because it gets too much rainfall.” 33

While it is true that strains of many crops can be found or developed that will grow in the rainier uplands, the common strains of many need a primarily sunny climate to thrive. As we start to grow the fruits and vegetables we now import, we will find many to be very picky about where they will grow. Some will need that sunny farmland of Ho’opili- UHWO. Once it is gone, it is gone.

An Extra 1,300 Acres of Food a Year

A world-recognized expert on corn has stated that “On the mainland and around the world, because of changes of season with long, freezing winters, farmers can grow only one crop of corn a year. In Waimanalo, limited because of the rain, a farmer can grow two crops a year. The north shore slopes can produce three a year, but the sunny ‘Ewa land [Ho’opili-UHWO] produces four. 34

There are probably 1000 acres of prime farmland at Ho’opili that developer D.R. Horton has not yet touched, and another 300 at UHWO. Because we can grow an extra crop at Ho’opili-UHWO every year, if we keep those lands in farming, we can get 1300 acres more of food every year. It won’t be long till we will desperately need it!

Need Separated Farmlands to Escape Disease and Pest Infestations

A final reason why Koa Ridge and Ho’opili-UHWO must be saved is to protect our farms in the future from spread of disease and crop-eating insect infestations. As the weather warms, in many places of the world we are seeing disease and pest infestations moving across contiguous farmlands, killing off everything, with no way to stop them. 35

With no freezing temperatures of winter to kill them off here in Hawai’i, in the future, we will need to have separated farming areas, such as at Waimanalo, Kahuku, North Shore slopes, Koa Ridge, Ho’opili-UHWO and Waianae, so that if an infestation strikes in one place, crops under attack in that place can be moved to another, at least until the pest levels drop to acceptable economic thresholds. Escaping pests will mean reduced pesticide application and increased yields once free from the problems. 36

Action Needed to Save Ho’opili and Koa Ridge

When Koa Ridge, Ho’opili and UHWO were approved for development, no one involved was aware of world population explosion and all of the problems it would cause for Hawai’i. Now that they are known, it is clear that we simply cannot afford to lose these farmlands. Our future survival will depend on their availability. If necessary, in order to secure our future survival, our government must condemn all of the so-far-undeveloped Ho’opili, UHWO, and Koa Ridge land, exercising the power of eminent domain, and keep it in farming perpetually.

Concluding Thoughts

These pages are just a beginning. They haven’t touched on so many things that need to be done. For instance, clearly the time is NOW to expand farm education in high schools and colleges, and to get young farmers onto the land. It’s time to be opening up farmland and to start growing locally all of the foods we now import. A good living can be made in farming. We will also need to develop ranges for cattle, and to re-establish our piggeries, chicken and egg farms, dairies, slaughter houses, and on and on and on.

There are estimates that when Captain Cooke arrived, there were as many as a million people living in these islands. 37

They fed themselves. We can do it again.

The first step is becoming aware. Becoming aware must quickly be followed by springing into action.

What can you do? For a start, talk about this. Send it to others. Send it also to your legislators and city council member. Tell them of your concern.

Then start thinking of how you can best participate in the new agriculture-oriented Hawai’i that must be created to meet this challenge.

Our future for mid-century and beyond can be this…

Or this. The choice is ours. But we must begin to act NOW.

ENDNOTES

1. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects,

The 2015 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables, United Nations, New York, 2015 p. 1

2.

“Food Production Must Double by

2050 to Meet Demand from World’s Growing Population, Innovative Strategies Needed to Combat Hunger, Experts Tell Second Committee” United Nations Meetings Coverage and Press Releases October 2009.

3.

Laura Parker, “To the Last Drop,” National Geographic, August 2016.

4.

U.N. Secy. General Antonio Guterres, “U.N. chief warns of strains on global water supplies” Honolulu Star-Advertiser, June 7, 2017. p. A-6.

5.

Maria Trimarchi, “Will the U.S. be a desert in 50 years?” http://science.howstuffworks.com/nature/climate-weather/atmospheric/us-desert-50-years1.htm and H. Eswaran, R. Lal and P. F. Reich, “Land Degradation: An overview” USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service p.1 https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/detail/soils/use/?cid=nrcs142p2_054028

6.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “2050: A third more mouths to feed, Food production will have to increase by 70 percent” 23 September 2009, Rome. http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/35571/icode/

7.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “2050: A third more mouths to feed, Food production will have to increase by 70 percent” 23 September 2009, Rome. http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/35571/icode/

8.

Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects,

The 2015

Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables, United Nations, New York, 2015.

9.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “2050: A third more mouths to feed, Food production will have to increase by 70 percent” 23 September 2009, Rome. http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/35571/icode/

10.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “2050: A third more mouths to feed, Food production will have to increase by 70 percent” 23 September 2009, Rome. http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/35571/icode/

11.

Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects,

The 2015 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables, United Nations, New York, 2015.

13.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs/Population Division World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables

14.

Renee Johnson, “The US Trade Situation for Fruit and Vegetable Products,” Congressional Research Service, December 1, 2016, p. 2. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL34468.pdf

15.

Laura Parker, “To the Last Drop,” National Geographic, August 2016, p. 92.

16.

Laura Parker, “To the Last Drop,” National Geographic, August 2016.p.92.

18.

Susan Craig, “California's drought is all but over, but some wells are still dry” May 29, 2017.

19.

Carolyn Lochhead, “California drought: Central Valley farmland on its last legs Years of irrigation have taken toll on San Joaquin Valley” SFGate Monday, March 24, 2014. http://www.sfgate.com/science/article/California-drought-Central-Valley-farmland-on-5342892.php

20.

Mark Bittman, “Everyone Eats There,” The New Yourk Times Magazine, Oct. 10, 2012.

21.

Carl Haub, “U.S. Population Could Reach 438 Million by 2050, and Immigration Is Key” Population Rerfernce Bureau, February 2008. http://www.prb.org/Publications/Articles/2008/pewprojections.aspx

22.

Star-Advertiser September 11, 2016

23.

In 2015, the state spent $10 million to acquire an additional 500 acres of agricultural land. (Duane Shimogawa Pacific Business News “Hawaii putting up $10M to acquire 500 acres of ag lands in Central Oahu, Jun 11, 2015.

http://www.bizjournals.com/pacific/news/2015/06/11/hawaii-putting-up-10m-to-acquire-500-acres-of-ag.html. And in 2106 the state purchased another 895 acres. Hawaii Senate Majority, Nearly 900 Acres of Farmland to be Preserved in Central O’ahu Honolulu. October 6, 2016, https://www.hawaiisenatemajority.com/single-post/2017/01/05/NEARLY-900-ACRES-OF-FARMLAND-TO-BE-PRESERVED-IN-CENTRAL-OAHU.

24.

Name withheld by request, in an email to Dr. Kioni Dudley dated Sunday 5/28/2017.

25.

Leon Sollenberger, in a personal note to Dr. Kioni Dudley emailed on May 24, 2017.

26. Leon Sollenberger, in a personal note to Dr. Kioni Dudley emailed on June 7, 2017.

27.

Anita Hofschneider, “As Hoopili Decision Looms, How Much Farmland Is Left?” Civil Beat, March 3, 2015.

http://www.civilbeat.org/2015/03/as-hoopili-decision-looms-how-much-farmland-is-left

The statement in the text above is a recalculation based on this original statement: “Datta estimated that an additional 19,000 acres of prime farmland are needed — in addition to the current 9,000 acres in production — to help Hawaii reach 80 percent self-sufficiency for fruits and vegetables.”)

28.

Mana K. Southichack, Ph.D., “Wahiawa Irrigation System Economic Impact Study” Agricultural Development Division, Hawaii Department of Agriculture, November 21, 2008, p. 5-6. http://hdoa.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/WIS-Econ-Impact-Study-2008.pdf On May 26, 2017, Marshall Lum, Asst. Director of Wastewater Branch of DOH, confirmed in a telephone conversation that one of the Waste Water Treatment Plants is still classified as R-2, so the prohibition is still in effect.

29.

“Measuring Housing Demand in Hawaii, 2015-2025” A report by the Hawaii Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism, Research and Economic Analysis Division March 2015 p. 24.

Honolulu Department of Planning and Permitting, ‘Ewa Development Plan, July 20`13 p.2-10;

30. “Honolulu Department of Planning and Permitting, Annual Report on the Status of Land Use on Oahu” 2008, pp. 6-7.

31.

Friends of Makakilo Exhibit #33, Land Use Commission 2012 p 2.

32.

Professor Linda Cox, Testimony at the Land Use Commission 3/1/12, p. 135:2-9.

33.

“UH tests chickpeas as food crop on 5 islands,” Star-Advertiser 6/20/2017 p.B-3.

34.

Professor James Brewbaker often told this to Dr. Kioni Dudley when he was alive.

35.

Katherine Mast “The Future of Food,” Discovery Magazine July/August 2017.

36. Jensen Uyeda, Extension Agent, UH CTARH, in email to Kioni Dudley on 3/23/2017.

37.

David E. Stannard, Before the Horror: The Population of Hawai'i on the Eve of Western Contact

(Honolulu: Social Science Research Institute, U of Hawaii, 1989) 66-6g.

Kioni Dudley, Ph.D., is a retired educator who lives in Makakilo, Hawai’i. He can be reached at (808) 672-8888. His email is DrKioniDudley@hawaii.rr.com